WORLD FUTURE FUND

http://www.worldfuturefund.org

INTRODUCTION DESCRIPTION CITIZEN

GUIDES READING

LIST SITE INDEX

REPORTS NEWS MULTIMEDIA

SEARCH HOW

TO CONTRIBUTE HELP WANTED

VOLUNTEERS

GRANTS

PUBLICATIONS

PRINCIPLES COPYRIGHT

NOTICE CONTACT

US

Editorial Note: This article was written in 2016. We plan to update this.

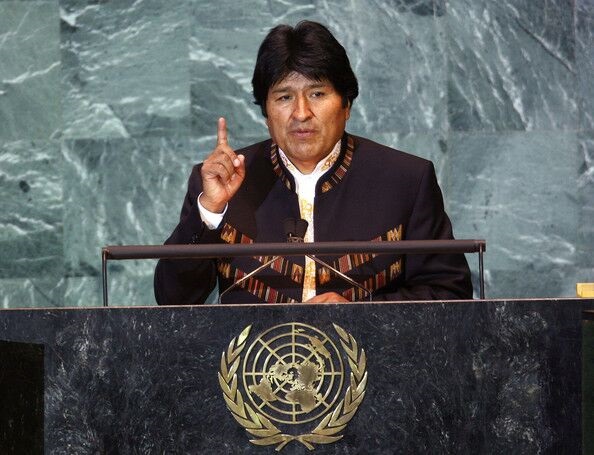

Evo Morales is the current President of Bolivia, and has been since 2006. He is widely regarded as the country's first president to come from the indigenous population, and his administration has focused on the implementation of leftist policies, the reduction of poverty, and combating the influence of the United States, as well as multinational corporations in Bolivia. As a democratic socialist, he is the current head of the Movement for Socialism (MAS) party. Morales is a controversial world figure, lauded by his supporters as a champion of indigenous rights, anti-imperialism and the environment. He has been praised for reducing poverty and bolstering literacy. He has also been internationally decorated with various awards. However, Morales has also been criticized from many perspectives on the political spectrum. Right-wing opponents have labelled his administration as authoritarian and radical, while leftist, indigenous and environmental critics have accused him of failing to live up to his espoused values. But regardless of what his critics say, he has truly had a unique presidency and has done much to advocate for the rights of the indigenous, the poor and the environment.

He was born to a family of subsistence farmers. Later he became a trade unionist for coca growers, and rose to prominence in the campesino (rural laborers union) campaigning against U.S. and Bolivian attempts to eradicate coca as part of the War on Drugs. He denounced U.S. actions as an imperial violation of the native indigenous, Andean culture. Coca has, after all, been cultivated in the medium altitude parts of the Bolivian Andes since the days of the Incan Empire (and perhaps even earlier). He repeatedly engaged in anti-government, direct action protests, and was arrested multiple times.

He entered politics in 1995 and became the leader of the MAS. He was also elected to Congress. His campaign focused on issues affecting the indigenous people and the poor. Morales was a big advocate for land reform and the redistribution of the country's gas wealth. Gaining increasing visibility through the Cochabama protests and gas conflict, in 2002 he was expelled from Congress for encouraging protesters, even though he came in second in that year's presidential elections.

In 2005 he was eventually elected president, and began his term in 2006. Morales increased taxation on the hydrocarbons industry in order to bolster social spending, he emphasized projects to spread literacy, along with fighting poverty, racism and sexism. In his presidency, he has been a very vocal critic of neoliberalism, and has reduced his country's dependence on the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. His administration oversaw a strong economic growth, while following a policy nicknamed "Evonomics." Evonomics sought to move from a liberal economic approach, to a mixed economy. Morales scaled back U.S. influence in the country, built relationships with the Leftist South American bloc, and added Bolivia to Hugo Chavez's Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas.

After winning a recall referendum in 2008, he put in place a new constitution that established Bolivia as a plurinational state, before being re-elected in 2009. In his second term, he witnessed the continuation of the leftist policies and Bolivia joining the Bank of the South and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean states.

LAW OF MOTHER EARTH - THE RIGHTS OF THE PLANET

One of Morales' most significant policies in his presidency is his strong support for the environment. Many countries in the West have an idea of "human rights." But what about the rights of other living beings? What about the biological rights of nature and life on the planet?

In October 2012, the government of Bolivia passed a Law of Mother Earth, a law designed to protect a number of rights for the planet. The law defines Mother Earth as a "collective subject of public interest," and declares both Mother Earth and life-systems (which combines human communities and ecosystems) as title holders of inherent rights specified by the law. Human beings and their communities are considered a part of Mother Earth, by being integrated into "life systems," defined as "...complex and dynamic communities of plants, animals, microorganisms and other beings in their environment."

The law invests Nature with seven specific rights: the right to life, the diversity of life, to water, to clean air, to equilibrium, to restoration and to living free of contamination.

However, one controversial aspect of the law is that it banned genetically modified organisms (GMOs) from being grown in Bolivia. Although this was supported by environmentalists, it was criticized by soya growers, who claimed that they would make less on the global market.

For more information, read Bolivian Law on Nature's Rights.

CHAVEZ AND MORALES COMMENT ON THE FAILURE OF PLUTOCRATIC ELITE TO BAIL OUT THE ENVIRONMENT

The "global south," developing countries, are disproportionately affected by climate change. Thus both Morales and Chávez had the following to say about the failure of the 2009 Copenhagen climate conference.

Bolivian President Evo Morales said, "The budget of the United States is US$687 billion for defense. And for climate change, to save life, to save humanity, they only put up $10 billion. This is shameful."

Hugo Chávez stated, "Do the rich think they can go to another planet when they've destroyed this one?" along with "If the climate were a bank, they would have bailed it out already."

THE ALLIANCE OF MORALES AND CHAVEZ

Evo Morales and Hugo Chávez maintained a close alliance and friendly rapport throughout the time they served their respective nations. Chávez provided substantial support for Morales’s initial election campaign in 2005, after which the Bolivian president launched many initiatives similar to those that distinguished Venezuela's Bolivarian Revolution: such as a dynamic literacy campaign, the nationalization of natural resources, land reforms, and other policies directed at social development. The two nations have played off one another's hopes for an integrated Latin America by vocally aligning themselves against U.S. foreign policy and economic intervention both regionally and worldwide. On October 14th 2014, when Morales was re-elected as president, he dedicated his victory to the late Hugo Chavez. (Venezuelan Analysis).

PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED NATION'S G77

Another formidable accomplishment of Morales is that he was the leader of the G77 for a year (between 2014-2015). The G77 is a coalition of developing nations at the United Nations that formed in June 15th, 1964. Today, this group has grown to include 133 members and now represents over two thirds of the world's population. In 2014, the coalition celebrated their 50th anniversary (on June 15, 2014) at the summit in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. 133 Member states showed up at the summit. UN Secretary General Ban-Ki-moon opened the event with an emphasis on the need to accelerate efforts to meet the goals of the summit (such as reducing the number of people living in poverty world wide). The theme of that year's summit was developing a "New World Order for Living Well." Global poverty and income inequality were a major issue of discussion. The G77 made a declaration to reduce poverty and inequality, promote sustainable development, protect the sovereignty over natural resources and promote fair trade and technology transfers. The coalition even proposed a new goal to eradicate extreme poverty within its member states by 2030.

Economic inequality was a major point in Morales's discussion, given that it is currently at its highest level in history. Today 15 multinational corporations control 50% of the global output. Morales brought up other crucial statistics, such as the fact that 0.1% of the world’s population owns 20% of the asset base of mankind. He also put income inequality in perspective by stating that in 1920, a US business manager made 20 fold the wage of a worker, and that now the difference is 331 fold.

For more information, read our G77 2014 Summit.

BOLIVIAN ECONOMIC PROGRAM

When Morales was elected to the presidency, Bolivia was South America's poorest nation. Morales' government did not initiate any dramatic change in Bolivia's economic structure, and in their National Development Plan for between 2006-2010, they adhered largely to the country's previous liberal economic model. Bolivia's economy was based largely on the extraction of natural resources, and have the second largest reserves of natural gas in South America. As part of Morales' election pledge, Morales took increasing state control over this hydrocarbon industry by imposing Supreme Decree 2870. Previously, corporations had paid 18% of their profits to the state. But Morales reversed this, so that 82% of the profits went to the state and 18% went to the corporations. The oil companies threatened to take the case to the international courts or cease operating in Bolivia, but ultimately they relented. And as a result, Bolivia received $173 million from hydrocarbon extraction in 2002. By 2006 they received $1.3 billion. Although this was not technically a form of nationalization, Morales and his government referred to it as such, and received criticism from sectors of the Bolivian left. However, in June 2006, Morales announced his plan to nationalize mining, electricity, telephones and railroads. In February 2007, he nationalized the Vinto metallurgy plant.

Under Morales, Bolivia experienced remarkable macroeconomic strength, resulting in the increase in the value of its currency, the boliviano. Morales' first year in office ended with no fiscal deficit. This was the first time this had happened in Bolivia for 30 years. And during the global financial crisis of 2007-2008, Bolivia maintained some of the world's highest levels of economic growth. This economic strength led to a national wide boom in construction, and allowed the nation to build up strong financial reserves. Although while levels of social spending increased, they remained relatively conservative, with a major priority being placed on constructing paved roads, as well as community spaces such as soccer fields and union buildings. The government in particular focused on rural infrastructure improvement, to bring roads, running water and electricity to areas that lacked these things.

Welfare provision was expanded, there was the introduction of non-contributory old-age pensions, and payments provided to mothers (as long as their babies were taken for health checks and their children attended school). Hundreds of free tractors were also handed out. The prices of gas and food were controlled, and local food producers were made to sell in the local market, rather than export. The new state-owned body was also set up to distribute food at subsidized prices. All these measures helped to curb inflation, while the economy grew strongly, with more public finances and increased economic stability.

During the first term of Morales, Bolivia broke free of the domination of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. In may 2007, Bolivia was the first country in the world to withdraw from the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes, with Morales asserting that the institution had consistently favored multinational corporations in its judgments. Bolivia's lead was followed by other South American nations as well. Also, ignoring encouragement from the U.S, Bolivia refused to join the Free Trade Area of the Americas, seeing it as a form of U.S. imperialism.

However, this vast economic growth did pose a dilemma to the Morales administration. The desire to expand extractive industries in order to fund social programs along with providing employment stood in stark contrast to the goal of protecting the environment from the pollution caused by these industries. On one hand, the Bolivian government professed a policy of environmental stewardship, expanded environmental monitoring and became a leader in the voluntary Forest Stewardship Council. Yet on the other hand, Bolivia continued to witness rapid deforestation for agriculture along with illegal logging.

SOCIAL REFORMS

Most countries today have a GDP, or some kind of model to measure economic development and growth. However, Morales wanted to encourage a model of social development based on the premise of vivir bien, or "living well." This involved seeking social harmony, consensus, the elimination of discrimination and the distribution of wealth. In doing so, there was a shift to communal, rather than individual values, which was based more on Andean forms of social organization rather than Western ones.

When Morales was elected, Bolivia's illiteracy rate was 16%, the highest in South America. In an attempt to rectify this with the aid of far left allies, Bolivia launched a literacy campaign with assistance from Cuba, while Venezuela invited 5,000 Bolivian high school graduates to study in Venezuela for free. By 2009, UNESCO declared Bolivia to be free from illiteracy, although the World Bank claimed that it had only declined by 5%. Cuba also aided Bolivia in the development of its medial care, and opened ophthalmological centers in the country to treat 100,000 Bolivians for free per year and offered 5,000 free scholarships for Bolivian students to study medicine in Cuba. The government expanded state medical facilities, opening twenty hospitals by 2014, and increased basic medical coverage up to the age of 25. Bolivia sought an approach of harmonizing both mainstream Western medicine and Bolivia's traditional medicine.

NATIVE RIGHTS

In order to reduce racism against the country's indigenous people, Morales announced that all civil servants were required to learn one of Bolivia's three indigenous languages: Quechua, Aymara, or Guarani within two years. His government also encouraged the development of indigenous cultural programs and sought to encourage more indigenous people to attend universities . Apparently this approach worked, because by 2008, it was estimated that half of the students enrolled in Bolivia's 11 public universities were indigenous people, while three indigenous-specific universities had been established, offering subsidized education. In 2009, a Vice Ministry for Decolonization was established, which passed the 2010 Law Against Racism and Discrimination, banning the espousal of racist views in private or public institutions.

THE WORKING CLASS

Policies were also put in place to improve the lives of the working class. Morales' government increased the legal minimum wage by 50%, and reduced the pension age from 65 to 60, and then in 2010 reduced it again to 58. A 2006 law also reallocated state-owed lands, with this agrarian reform entailing distributing lands to traditional communities rather than individuals. However, while many policies helped the poor, some middle-class Bolivians felt that they had seen their social standing decline.

DEPATRIARCHALIZATION - EXPANDING LGBT AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS

Morales' administration also worked to improve women's rights. In 2010, it founded a Unit of Depatriarchalization in order to oversee this process. There was also an expansion of the support of LGBT rights. Bolivia declared June 28 to be Sexual Minority Rights Day in the country, and even encouraged the establishment of a gay-themed television show on the state channel.

RELATED CONTENT ON WORLD FUTURE FUND

Bolivian Law on Nature's Rights

LEGAL DOCUMENTS

Supreme Decree 2870 (PDF)

A legal document issued by Evo Morales to put forth a political framework for nationalization of industry.

SPEECHES

Speech by Evo Morales at G77 2014

History at the Barricades: Evo Morales and the Power of the Past in Bolivian Politics (Excerpt) (NACLA, 10-8-19)

Evo Morales’ historic speech at the Isla del Sol (Life on the Left, 1-1-13)

NEWS STORIES

Bolivia's Morales blames capitalism for climate change (Aljazeera, 10-13-15)

US Targets Bolivia With Secret Drug Indictments Against Evo Morales’ Government (Mint Press News, 9-23-15)

Evo Morales has proved that socialism doesn’t damage economies (The Guardian, 10-14-14)

Poverty, Climate Change and Indigenous Rights In Morales and Menchu Speeches (Indian Country Today, 10-5-14)