WORLD FUTURE FUND

http://www.worldfuturefund.org

INTRODUCTION DESCRIPTION CITIZEN

GUIDES READING

LIST SITE INDEX

REPORTS NEWS MULTIMEDIA

SEARCH HOW

TO CONTRIBUTE HELP WANTED

VOLUNTEERS

GRANTS

PUBLICATIONS

PRINCIPLES COPYRIGHT

NOTICE CONTACT

US

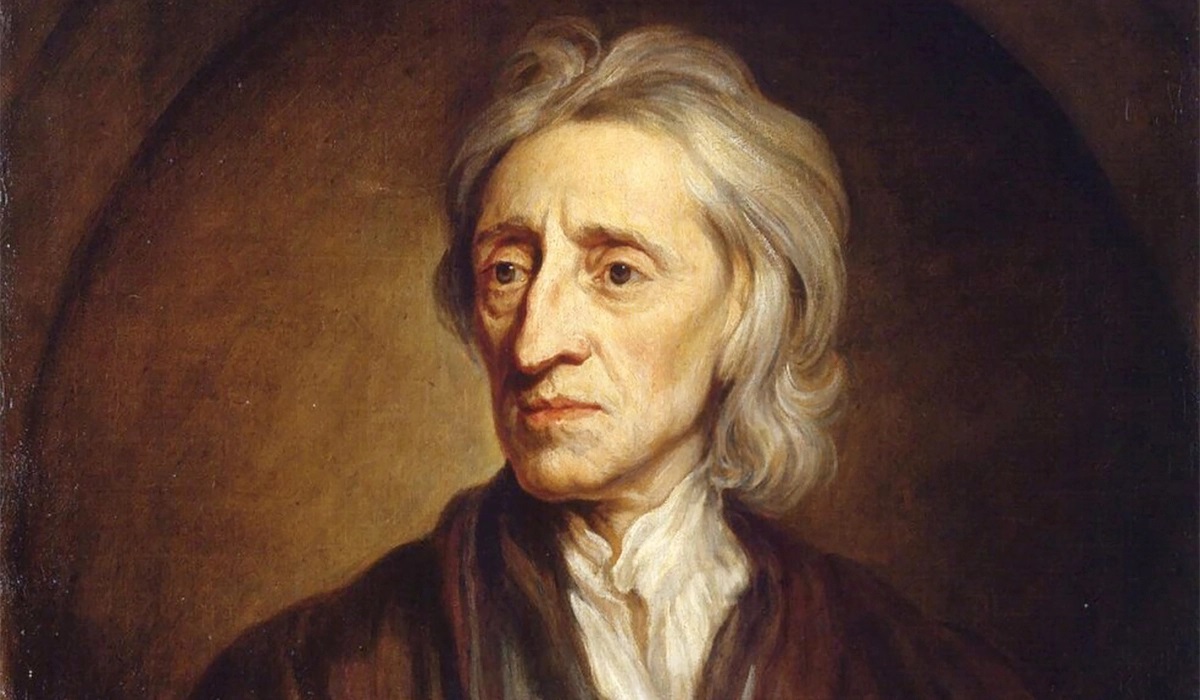

Did the 17th century English philosopher John Locke truly support freedom for all, or was it just freedom for some?

John Locke is widely regarded as one of the most important philosophers in the development of modern liberal thought, and his ideas on natural rights, government, and the social contract were influential in the American and French Revolutions. John Locke’s Second Treatise on Government and Letters on Toleration set out the case for a limited government and respect for private property rights.

However, after taking an in depth look at both his life and written works, some say there is a blatant level of hypocrisy concerning his ideas on freedom.

Did John Locke Support Slavery?

Locke was heavily involved in the slave trade, both through his investments and his administrative supervision of England’s burgeoning colonial activities. This is discussed further in The Contradictions of Racism by Bernasconi and Mann.

John Locke owned stocks in the English slave trade, specifically the Royal African Company and the Bahama Adventurers Company. As the official clerk for Charles II's Council on Foreign Plantations, he was paid in Royal African Company Stock between 1672-1673. However, later Locke became an outspoken critic against Charles II, fled to France and sold his Royal African Stock in 1675.

Another issue is that Locke authored The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina (1669), which explicitly supported hereditary nobility and slavery.

Bernasconi and Mann offer evidence that Locke changed a key sentence in the Fundamental Constitution of the Carolinas. The sentence originally read that “every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute Authority over his Negro slaves,” which is disturbing enough. But it was changed by Locke to read that “every freeman shall have absolute power and Authority” – a change that, as Bernasconi and Mann note, arguably made it easier for slaveholders to torment and even kill the people they held in bondage.

It is said that John Locke himself did not openly support hereditary slavery and opposed it on the same grounds as hereditary monarchy. Locke’s First Treatise begins with the following, "SLAVERY is so vile and miserable an estate of man, and so directly opposite to the generous temper and courage of our nation; that it is hardly to be conceived, that an Englishman, much less a gentleman, should plead for it." However, an argument has been made that this wasn't an absolute condemnation of all slavery. Jacobin magazine elaborates further, "In fact, however, it [the quote on slavery] is more appropriately understood as an early rendition of the jingoism expressed in the sentiment that 'Britons never, never, never, shall be slaves.' Locke’s intention, in this passage, was to demolish the idea of Sir Robert Filmer that Englishmen (including English Americans) could voluntarily agree to submit to a government with the absolutist claims of the Stuarts — it was this submission to which the term 'slavery' referred."

However, he did support slavery of those who committed a crime or were captives of war:

"Indeed, having by his fault forfeited his own life, by some act that deserves death; he, to whom he has forfeited it, may (when he has him in his power) delay to take it, and make use of him to his own service, and he does him no injury by it: for, whenever he finds the hardship of his slavery outweigh the value of his life, it is in his power, by resisting the will of his master, to draw on himself the death he desires.

(Section 23 John Locke's Second Treatise on Government)."

"This is the perfect condition of slavery, which is nothing else, but the state of war continued, between a lawful conqueror and a captive: for, if once compact enter between them, and make an agreement for a limited power on the one side, and obedience on the other, the state of war and slavery ceases, as long as the compact endures: for, as has been said, no man can, by agreement, pass over to another that which he hath not in himself, a power over his own life (Section 24 John Locke's Second Treatise on Government)."

The problem with justifying slavery for captives of war is that Africans were frequently enslaved as a result of war, and there was no reason to suppose this war to be just.

Did John Locke Support Religious Rights For All or Not?

It has been pointed out in John Locke's A Letter Concerning Toleration, there is language that could be used to exclude Atheists, Catholics and Muslims.

On Atheists, he writes, "Lastly, those are not at all to be tolerated who deny the being of a God. Promises, covenants, and oaths, which are the bonds of human society, can have no hold upon an atheist. The taking away of God, though but even in thought, dissolves all; besides also, those that by their atheism undermine and destroy all religion, can have no pretence of religion whereupon to challenge the privilege of a toleration."

However, he also adds, "As for other practical opinions, though not absolutely free from all error, if they do not tend to establish domination over others, or civil impunity to the Church in which they are taught, there can be no reason why they should not be tolerated."

Also while he states early in his letter that a Catholic does no harm to his neighbor by eating "the body of Christ which another man calls bread," he does indirectly bring up what he sees as problems with Catholicism and Islam in that the members of these faiths follow foreign leaders:

"Again: That Church can have no right to be tolerated by the magistrate which is constituted upon such a bottom that all those who enter into it do thereby ipso facto deliver themselves up to the protection and service of another prince. For by this means the magistrate would give way to the settling of a foreign jurisdiction in his own country and suffer his own people to be listed, as it were, for soldiers against his own Government. Nor does the frivolous and fallacious distinction between the Court and the Church afford any remedy to this inconvenience; especially when both the one and the other are equally subject to the absolute authority of the same person, who has not only power to persuade the members of his Church to whatsoever he lists, either as purely religious, or in order thereunto, but can also enjoin it them on pain of eternal fire. It is ridiculous for any one to profess himself to be a Mahometan only in his religion, but in everything else a faithful subject to a Christian magistrate, whilst at the same time he acknowledges himself bound to yield blind obedience to the Mufti of Constantinople, who himself is entirely obedient to the Ottoman Emperor and frames the feigned oracles of that religion according to his pleasure. But this Mahometan living amongst Christians would yet more apparently renounce their government if he acknowledged the same person to be head of his Church who is the supreme magistrate in the state."

Did John Locke Support Land Seizure from Native Americans?

The American Indian Law Journal dives into this question in their article, "John Locke's Theory of Property and the Dispossession of Indigenous Peoples in the Settler-Colony." The paper explores how John Locke's theory of property, elaborated upon in his Second Treatise on Government, provided justification for the appropriation of indigenous land.

In his Second Treatise on Government, Locke states, "Thus in the beginning all the World was America," inadvertently making the continent of America part of Western political philosophy.

The American Indian Law Journal also points out that John Locke's "state of nature" refers to people living in a natural state before entering into a political society, and that the rights of people living in a so called natural state are different than those living in a political society. A potential implication of Locke's arguments is that the laws of indigenous people are not legitimate, and their property can be seized. Indeed, many of the prominent English settlers in the American settler-colonies, such as Samuel Parchas and John Winthrop (founder of the Massachusetts Bay Colony), argued that treaties with First Nations were invalid since treaties could only be enacted by legitimate state institutions, which the Natives were deemed to lack (The American Indian Law Journal).

Locke defended large-scale property holders against the idea that people have the right to common land. “I shall endeavour to shew,” Locke wrote in his Second Treatise, “how men might come to have a property in several parts of that which God gave to mankind in common, and that without any express compact of all the commoners” – in other words, how land could be seized by the few, against the will of the many. He also refers to Native Americans as as “tenants” of the common land.

Locke argued that the publicly-shared commons can become private property when somebody adds value to it. He doesn’t explain how powerful landowners, who don’t do any actual labor themselves, meet this already-questionable test.

Read John Locke's Work

A Letter Concerning Toleration

About John Locke

Scholarly Articles

The Contradictions of Racism (Robert Bernasconi & Anika Maaza Mann)

"John Locke's Theory of Property and the Dispossession of Indigenous Peoples in the Settler-Colony. (American Indian Law Journal, 1-25-22)

‘This man is my property’: Slavery and political absolutism in Locke and the classical social contract tradition (Sage Journals, 3-30-20)

Essays

John Locke, Catholicism, and the American Founding (National Review, September 2019)

THE LOCKEAN ROOTS OF WHITE SUPREMACY IN THE U.S. (Foreign Policy in Focus, 3-10-21)

John Locke Against Freedom (Jacobin, 6-28-15)

Related World Future Fund Pages